A Day in a Medieval Village in Italy: Life in the 1200-1300s (Time Travel with RomeCabs)

Greetings and welcome to the RomeCabs Italy Travel Blog! With so many wonderfully preserved medieval towns across Italy, it’s natural to wonder what a day in a medieval village in Italy might have looked like during the 1200s and 1300s. Life in an Italian village was an intricate blend of routines and traditions, deeply tied to the rhythms of nature, the cycles of agriculture, and the feudal structures that defined society.

Villagers’ daily lives were centered around community, religious devotion, and their close connection to the land, which provided for all their essential needs. While life in a medieval Italian village was often harsh and labor-intensive, it was shaped by a sense of stability, purpose, and continuity passed down through generations.

Before we journey back in time to “spend a day in a medieval village in Italy in the 1200-1300s” here are some important aspects that characterized life during this period and the historical developments to better understand medieval village life:

What was Medieval Life like in the 1200s-1300s?

1. The Feudal System: Defining the Structure of Medieval Village Life

In the 1200s and 1300s, the feudal system was a defining feature of rural life in Italy and much of Europe. Villages were typically part of a larger manorial estate controlled by a local lord or noble. This system created a structured hierarchy where peasants, or serfs, were bound to the land and required to provide labor or produce in exchange for protection and the right to work their plots.

The feudal relationship deeply influenced daily activities, as most villagers focused on fulfilling their duties to the lord. From tending crops to maintaining the lord’s lands, their work was structured around obligations, which often left little room for personal pursuits. While this system was restrictive, it also provided a sense of security, as the lord offered protection against external threats and maintained order within the village.

2. Agricultural Developments: Increasing Yields and Stability

The 1200s and 1300s saw notable advancements in medieval agricultural practices, which significantly impacted village life. One of the most important innovations was the three-field system. In this system, land was divided into three parts: one planted in autumn, one planted in spring, and one left fallow to recover. This crop rotation method allowed for better soil fertility and increased yields, reducing the frequency of food shortages and allowing for modest population growth.

These agricultural improvements meant that villagers could produce more food and, in turn, have some surplus to sell or barter in local markets. This period also saw the development of more efficient farming tools, such as the heavy plow, which made it easier for farmers to till the soil and manage larger areas. As a result, agriculture began to support a more stable lifestyle, and the threat of famine decreased, leading to a gradual increase in the population and greater economic opportunities.

3. Religious Influence: The Spiritual Heart of the Village

Religion played a central role in medieval Italian villages, and the Church was the spiritual, moral, and social center of daily life. The local church, often the tallest and most substantial building in the village, was where villagers gathered for Mass, feast days, and religious celebrations. The Church calendar, filled with feast days, holy days, and periods of fasting, structured the villagers’ year and created a shared sense of community and devotion.

During the 1200s and 1300s, the rise of mendicant orders such as the Franciscans and Dominicans brought more active religious engagement to these villages. These monks and friars traveled through the countryside, preaching, providing aid, and encouraging villagers to lead virtuous lives. Their presence helped deepen the influence of the Church on daily life, offering spiritual guidance and moral teachings. Villagers looked to the Church not only for religious fulfillment but also for advice on social and moral matters.

4. Trade and Market Expansion: Connecting Villages to the Wider World

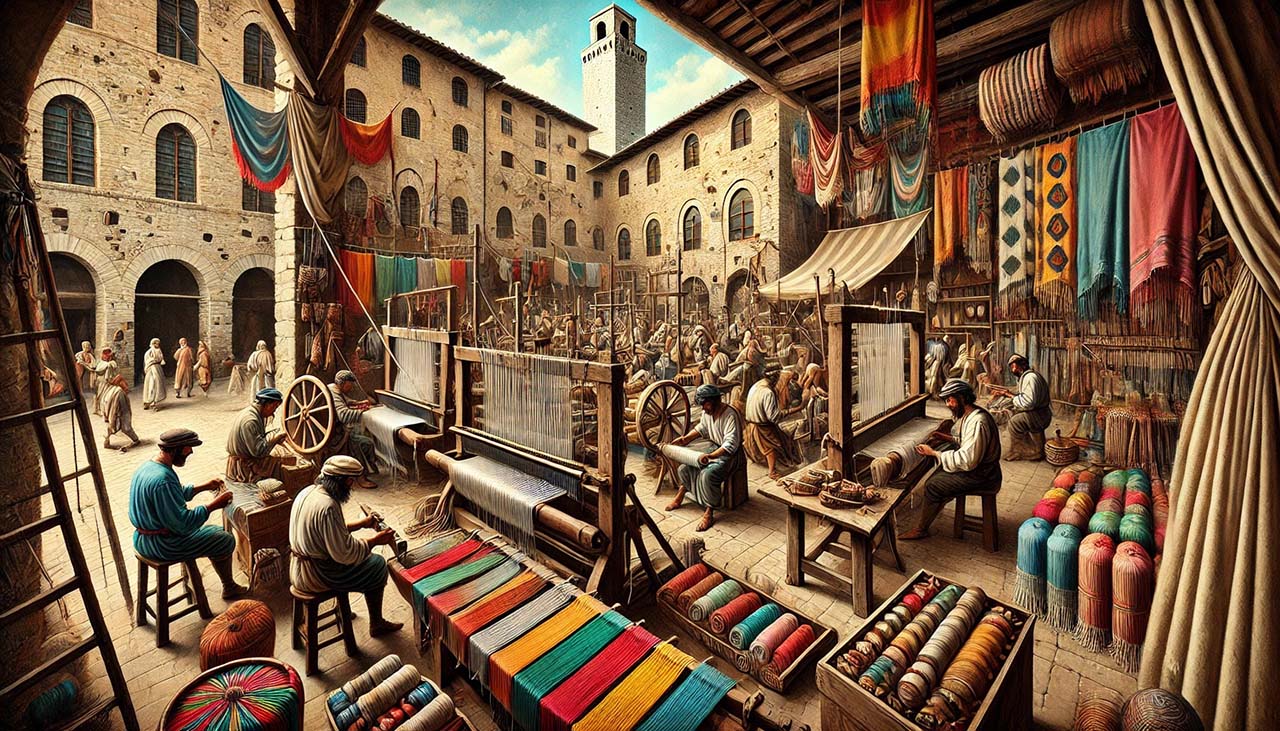

The 1200s and 1300s were a time of expanding trade and growing markets. Italian villages, especially those near bustling towns or along trade routes, began to sell surplus produce and artisanal goods in local and regional markets. This period saw the growth of fairs and markets, which brought traders from afar, enriching village life with new products, spices, and materials that were otherwise inaccessible.

Thanks to Italy’s geographic position, villages close to trade routes benefited from exposure to distant cultures. Traders brought luxury items such as silks, spices, and finely crafted tools, offering villagers a glimpse into goods and customs from beyond their borders. For many, these markets were a lively gathering place where they could sell their produce, buy necessities, and catch up on news from the outside world.

5. Social Structure and Changes: Shifting Opportunities for Villagers

While the social structure of a medieval village remained strictly hierarchical, the 1200s and 1300s saw the beginnings of social mobility for those who could accumulate wealth through trade or skilled work. The rise of a merchant class in towns provided new opportunities for some villagers who aspired to greater independence and a better quality of life.

In rare cases, skilled artisans or successful farmers might amass enough wealth to move to a nearby town, where social advancement was more attainable. This emerging class system allowed those with ambition and resources to dream of a life beyond the constraints of serfdom. However, such mobility was still limited and rare, and most villagers continued to live within the rigid boundaries of the feudal order.

6. Architecture and Village Layout: A Simple but Functional Design

Medieval Italian villages in the 1200s and 1300s typically had a simple yet functional layout, with narrow, winding streets centered around a church, manor house, and common areas like the village square. Houses were typically small and built from local materials such as wood, stone, and thatch. Each home served multiple purposes, with family members, livestock, and stored crops all sharing space under one roof.

By the late 1200s, wealthier villages and those near prominent trade routes began to incorporate more substantial stone buildings, a sign of increasing prosperity and architectural development. This shift not only improved the durability of homes but also marked a visible distinction in social status, as wealthier families could afford these sturdy structures. The church, however, often remained the most architecturally significant building, reflecting its importance in the community.

7. The Constant Threat of War and Conflict: Villagers’ Lives on Edge

During the 1200s and 1300s, medieval Italy was frequently embroiled in conflict, from local feuds between noble families to broader territorial wars and incursions by foreign powers. Villagers lived with the constant threat of raids or forced conscription, and many times, they were required to flee their homes for safety. Fortifications, such as walls and towers, were sometimes added to villages, offering some protection but also a reminder of the volatility of the era.

The ever-present possibility of violence shaped the psychology of the village. Villagers often lived in a state of preparedness, learned basic defense, and were aware of nearby safe havens or escape routes. Despite the hardships of rural life, their sense of community and solidarity helped them endure these periods of uncertainty.

Let’s journey back to this period to explore what a typical day in such a village might have looked like, while also considering the broader historical context and developments of the time.

A Day in a Medieval Village in Italy: Life in the 1200-1300s

Dawn: The Village Awakens

In the stillness of the early morning, before the first light of dawn touches the horizon, a medieval village begins to stir. The village is small, nestled in a valley or perched on a hillside, surrounded by fields and forests that provide sustenance and protection.

The homes, built from local materials like stone, wood, and thatch, are clustered together for warmth and security. Their small, thick-walled structures huddle around the village square, where the church bell tower rises above all else, serving as a constant reminder of the divine presence that governs their lives.

As the first rays of the sun break through, the roosters crow, and the day begins. The air is cool, the sky still tinged with the colors of night, but the village is already coming to life. Inside these modest homes, villagers rise from their simple straw mattresses, their breath visible in the cold morning air. The hearth, which has smoldered through the night, is stoked back to life, providing warmth and a place to cook the day’s first meal.

The church bell tolls, calling the villagers to early morning prayers. For many, this is how each day begins, with a visit to the church at the center of the village. The church, often the only stone building in the village besides the manor house, is not just a place of worship but the spiritual heart of the community. It is where the villagers are baptized, married, and ultimately, where they will have their final rites. The priest, a central figure in village life, leads the morning prayers, asking for blessings and protection for the day ahead.

Morning: The Village Buzzes with Work and Trade

After prayers, the village truly comes alive. The sun is now fully risen, casting long shadows across the fields and illuminating the dew-covered grass. The village is bustling with activity as each person goes about their daily tasks, all contributing to the communal life.

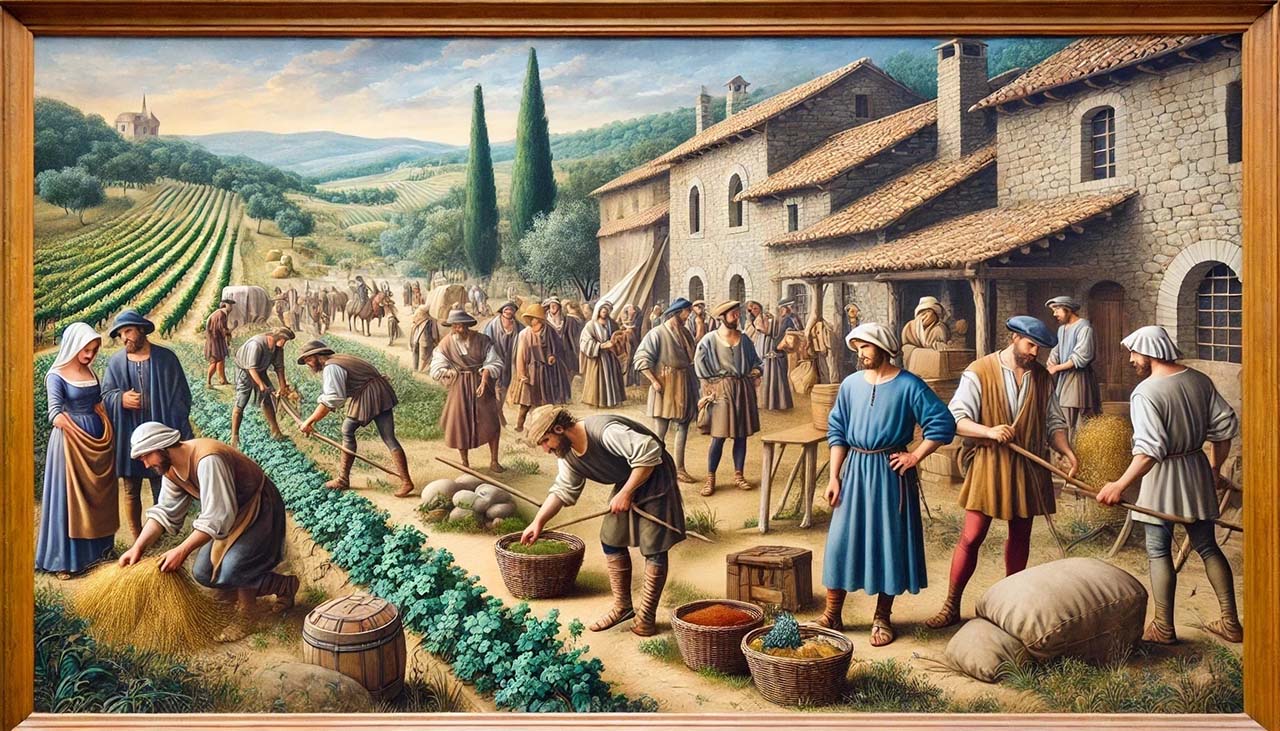

The majority of the villagers are peasants, and their lives are governed by the agricultural calendar. They work the land, growing crops like wheat, barley, and oats, or tending to vineyards and olive groves. The introduction of the three-field system during this period, where one-third of the land is left fallow each year to regain its fertility, has allowed for more efficient farming. This system, along with the use of more effective plows, has increased agricultural productivity, making famine less frequent and supporting modest population growth.

In the fields, men, women, and children work together. The men handle the heavier tasks, such as plowing and sowing, while the women help with planting, weeding, and tending the gardens. Children assist where they can, learning the skills they will need as adults. The work is hard, but the villagers understand that their survival depends on the land. The produce they harvest will not only feed their families but also fulfill their obligations to the local lord.

This is a feudal society, and the villagers are bound to the land they work. The local lord, who may live in a fortified manor house or nearby castle, owns the land and the villagers work it in exchange for protection and the right to live on it. They owe the lord a portion of their harvest, which is stored in the village granary or transported to the lord’s estate. These feudal obligations are central to the villagers’ lives, and failure to meet them can result in severe punishment.

While the farmers toil in the fields, the artisans and tradespeople are busy in their workshops. The village blacksmith’s forge glows red-hot as he shapes iron into tools, horseshoes, and weapons. The carpenter’s workshop is filled with the scent of freshly cut wood as he crafts furniture, barrels, and carts.

Weavers work their looms, producing cloth from wool or flax, which will be sewn into garments by the village women. These artisans are essential to village life, providing the goods and tools necessary for daily survival.

The village square, typically centered around a well or market cross, becomes a hub of activity as the morning progresses. Here, the village market takes place, where goods are traded and sold. Farmers bring their surplus produce, women offer eggs, cheese, and butter, and the local baker sells fresh bread.

The market is not just a place of commerce but a social gathering spot where villagers exchange news, gossip, and stories.

In this period, trade is expanding, especially with the growth of nearby towns and cities. Villages like this one benefit from this expansion, as they can sell their surplus produce or artisanal goods in local markets or to traveling merchants.

The rise of fairs and markets during the 1200s and 1300s brings traders and goods from afar, introducing villagers to new products and ideas. However, for most villagers, the market is where they procure their everyday needs and maintain the social fabric of their community.

Noon: A Time for Prayer and Rest

By midday, the sun is high, and the pace of work slows. The church bell rings once more, signaling the time for the Angelus, a prayer marking the Incarnation. Villagers pause their work to pray, whether in the fields, the market, or their homes. The Angelus is a moment of reflection, a brief respite in the busy day, and a reminder of the villagers’ deep religious faith.

Following the Angelus, it is time for the main meal of the day. In wealthier households, this meal might be more substantial, including bread, cheese, cured meats, and perhaps a stew made from vegetables, beans, and occasionally meat.

For most villagers, however, the meal is simple—bread, cheese, and a vegetable soup or porridge. Wine, often diluted with water, is the common drink, as it is safer than water alone. This is a time for families to gather, share food, and rest before returning to their tasks.

After the meal, there is a period of rest. The midday heat, especially in the summer, makes this a good time to stay indoors or seek the shade. Villagers might take a short nap, chat with neighbors, or simply relax before the afternoon’s work begins.

This break is an essential part of the day, offering a moment of peace in the otherwise demanding rhythm of village life.

Afternoon: Villagers Head Back to Work

As the afternoon wears on, the village returns to its work. The farmers head back to the fields to finish the day’s tasks, while artisans continue their work in their workshops. The village is a hive of activity once more, with everyone contributing to the community’s well-being.

Children, too, have their roles. While they might spend part of the day playing with simple toys made from wood or cloth, they also help with household chores or tend to the animals. Education is informal, with children learning skills from their parents.

Boys often learn their father’s trade, whether it be farming, blacksmithing, or carpentry, while girls are taught domestic skills like cooking, weaving, and spinning by their mothers. Only a few children, usually from wealthier families, receive formal education, often provided by the local priest or a traveling tutor.

The village council, composed of elders or leading citizens, might meet during the afternoon in the council hall or a designated meeting place. These meetings are crucial for maintaining order and addressing communal concerns.

Disputes over land, resources, or feudal obligations are resolved, and decisions are made regarding the organization of the market, the distribution of common land, and other matters affecting the village. This self-governance is vital to the village’s stability, ensuring that the needs of the community are met and that justice is upheld.

While the village is generally peaceful, the period from 1200 to 1300 is also marked by frequent conflicts. Local lords might engage in territorial disputes, or the village could be threatened by raids from rival factions or foreign invaders.

The constant threat of war and conflict means that villagers must be prepared to defend themselves. Some villages are fortified with walls or towers, and the local lord might call upon the men of the village to serve as soldiers. This ever-present danger added uncertainty to daily life, reminding the villagers that their safety is never guaranteed.

Evening: The Day Winds Down

As the sun begins to set, the village gradually quiets down. Farmers return from the fields, artisans close their workshops, and the market winds down. The evening meal is simpler than the midday feast, often consisting of leftovers, porridge, or a thin soup. This is a time for families to come together, share stories of the day, and prepare for the night ahead.

Evenings in the village are a time for socializing and communal activities. Villagers might gather in the square or in each other’s homes, where storytellers recount tales of heroes, saints, and local legends. Music is a common form of entertainment, with villagers playing simple instruments like flutes, drums, or lutes. Dancing is another popular pastime, with everyone joining in to celebrate the end of another day’s work.

For the devout, the day ends as it began, with prayer. The church bell rings one last time, calling the villagers to evening prayers.

Those who do not attend might say their prayers at home, offering thanks for the day’s blessings and seeking protection through the night. Faith is a constant companion in their lives, providing comfort and a sense of order in a world that can be harsh and unpredictable.

Night: The Village Sleeps

As darkness falls, the village settles into silence. The streets are deserted, and the only sounds are the occasional hoot of an owl or the rustling of the wind through the trees. Homes are secured for the night, with wooden shutters drawn and doors bolted. Families sleep close together, their homes providing a small but sturdy shelter against the outside world.

The village, though small and seemingly isolated, is a world unto itself. It is a place where life is governed by the rhythms of nature, the cycles of the seasons, and the traditions passed down through generations. Each day brings its challenges and rewards, but through hard work, faith, and the support of the community, the villagers find a sense of purpose and belonging in this medieval world.

Though centuries have passed, the echoes of medieval village life still resonate in rural Italy today. The values of community, hard work, and a deep connection to the land continue to shape the lives of those who live in these ancient landscapes. The fields that once fed the villagers, the stone churches that stood as spiritual bastions, and the cobbled streets that echoed with the sounds of daily life all remain as silent witnesses to a way of life that, while long gone, still informs the character and culture of the Italian countryside.

In the villages of the 1200s and 1300s, life was a delicate balance of work, faith, and community, all under the ever-watchful eyes of nature and the divine. It was a life where each day was a testament to human resilience and the enduring power of tradition.

Find RomeCabs also online:

RomeCabs Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RomeCabsToursAndTransfers

RomeCabs Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.it/romecabs

RomeCabs Twitter: https://twitter.com/RomeCabs

RomeCabs Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/romecabs/

RomeCabs Flickr Photo Gallery: https://www.flickr.com/photos/romecabs/