A Day in a Medieval Village in Italy: San Gimignano in the 1300s

Buongiorno, and welcome to the RomeCabs Italy Travel Blog! Today, we invite you to experience a day in a medieval village in Italy by stepping back in time to San Gimignano in the 1300s. Located in the heart of Tuscany, this village is now famous for its medieval towers and enchanting atmosphere, drawing visitors from all over the world. However, in the 1300s, San Gimignano was a bustling hub of daily life, where the rhythms of work, faith, and community intertwined to create a vibrant tapestry of medieval existence.

Let’s explore what life was like in this remarkable village and imagine what a typical day in San Gimignano might have been like during this fascinating period in history.

What was Medieval San Gimignano like during the 1300s?

During the 1200s and 1300s, San Gimignano would have been a vibrant and bustling town, brimming with economic activity and cultural life. The presence of towers, walls, and narrow, winding streets would have created a sense of both security and communal living. The town’s residents, ranging from wealthy merchant families to skilled artisans, farmers, and tradespeople, contributed to a diverse and dynamic community.

The constant flow of pilgrims and traders ensured that San Gimignano was never entirely cut off from the broader currents of medieval European life, making it a unique and important location during this period.

In the 1200s to 1300s, San Gimignano was a bustling medieval town situated on a hill in the heart of Tuscany, Italy. It was strategically located along the Via Francigena, a major pilgrimage route connecting Northern Europe to Rome, which brought in a mix of travelers, traders, and pilgrims. The town’s layout and architecture were heavily influenced by its medieval roots, characterized by narrow, winding streets, fortified walls, and an abundance of tall stone towers that dominated the skyline.

San Gimignano’s Medieval Walls and Towers

San Gimignano was most famous for its numerous tall towers, which gave it the nickname “Medieval Manhattan.” These towers were built by the wealthy merchant families as symbols of power, prestige, and wealth. In the 1200s, there were up to 72 towers, although today only 14 remain. The towers served both defensive purposes and were a clear indication of the intense rivalry between the town’s noble families, each competing to build a taller, more imposing tower.

The towers were constructed from stone, and they varied in height, with some reaching up to 50 meters (164 feet). They were square in shape, narrow, and built as freestanding structures next to family homes or palaces. Inside, they were often dark and sparse, with few windows to provide security against attacks.

.

The town was enclosed by robust stone walls, built for defense against potential invaders and rival towns. The walls were punctuated with several fortified gates, such as the Porta San Giovanni and Porta San Matteo, which controlled access to the town. The gates were imposing structures, often reinforced with wooden doors and iron fittings, guarded by town watchmen who monitored the comings and goings of visitors and residents.

San Gimignano’s social and economic life revolved around its central piazzas. The Piazza della Cisterna and the Piazza del Duomo were the two main squares in the town.

San Gimignano housed several important civic buildings, reflecting its status as a prosperous and semi-autonomous medieval commune. The Palazzo Comunale (Town Hall), which housed the town’s governing council, was a significant building featuring a large council chamber, meeting rooms, and a tower from which announcements could be made. The Palazzo del Podestà was another key structure, serving as the residence of the town’s leading magistrate. It was a grand building, often used for receptions and official functions.

Dawn in San Gimignano in the 1300s: The Day Begins

As the first light of dawn breaks over the Tuscan hills, the village of San Gimignano, perched atop its hill, stirs to life. The village, known for its impressive stone towers reaching into the sky, begins the day in relative quiet. The air is crisp, and a thin mist clings to the fields and vineyards that surround the village walls. Inside the fortified town, cobblestone streets lie still, but this calm does not last long.

The bell of the Collegiate Church, standing proudly in the center of the village, tolls to signal the start of a new day. The sound resonates through the narrow streets and alleys, bouncing off the high walls of stone houses and echoing down into the valley below.

.

Morning Routines: Rising with the Bell

For the villagers, this is the cue to rise. They wake from their beds, which are often simple straw mattresses laid on wooden frames. The wealthy may have feather-filled mattresses and linen sheets, but most villagers sleep on straw or wool-stuffed sacks. In the dim light, families gather around the hearth, which has been kept smoldering throughout the night.

The fire is stoked back to life, providing much-needed warmth and a place to prepare a simple breakfast. This might consist of porridge made from grains or bread baked the previous day, sometimes flavored with herbs or a little honey if available.

The Farmers’ Day of Tending to the Land

Farmers are among the first to rise and leave their homes. The land is the lifeblood of San Gimignano, and agriculture forms the backbone of the village economy. These early hours are crucial for work in the fields, where much depends on the season. In spring, they might be plowing and sowing the fields with wheat or barley, using heavy wooden plows drawn by oxen.

In the hot summer months, it’s time for weeding and tending to the growing crops, while autumn brings the harvest of grapes and olives, vital staples for both local consumption and trade.

The farmers head to their fields outside the village walls. They walk along narrow dirt paths, leading donkeys laden with tools and baskets for gathering crops. Wheat, olives, and grapes are the primary crops cultivated here.

Wheat is ground into flour for bread, the essential food staple of the medieval diet. Olives are pressed for oil, used in cooking and as a source of light in simple oil lamps. Grapes, of course, are turned into wine, which is safer to drink than water and forms an essential part of both daily meals and religious ceremonies.

Women often accompany the men, particularly during the harvest season, working side by side to gather the crops that will sustain their families through the year.

Inside the Village Walls, The Artisans are at Work

Meanwhile, within the village walls, the artisans and tradespeople begin to open their workshops. Each street seems to have its specialty: one lined with the rhythmic clang of the blacksmith’s hammer striking iron, another filled with the scent of fresh bread wafting from the bakeries. The blacksmiths ignite their forges, using bellows to fan the flames and heat the metal until it glows red-hot.

They skillfully shape the iron into tools, horseshoes, and occasionally, weapons. Across the way, bakers knead dough for the day’s bread, shaping it into rounds and sliding it into large communal ovens. Bread is a daily staple, and the ovens are kept hot from before dawn until well after sunset.

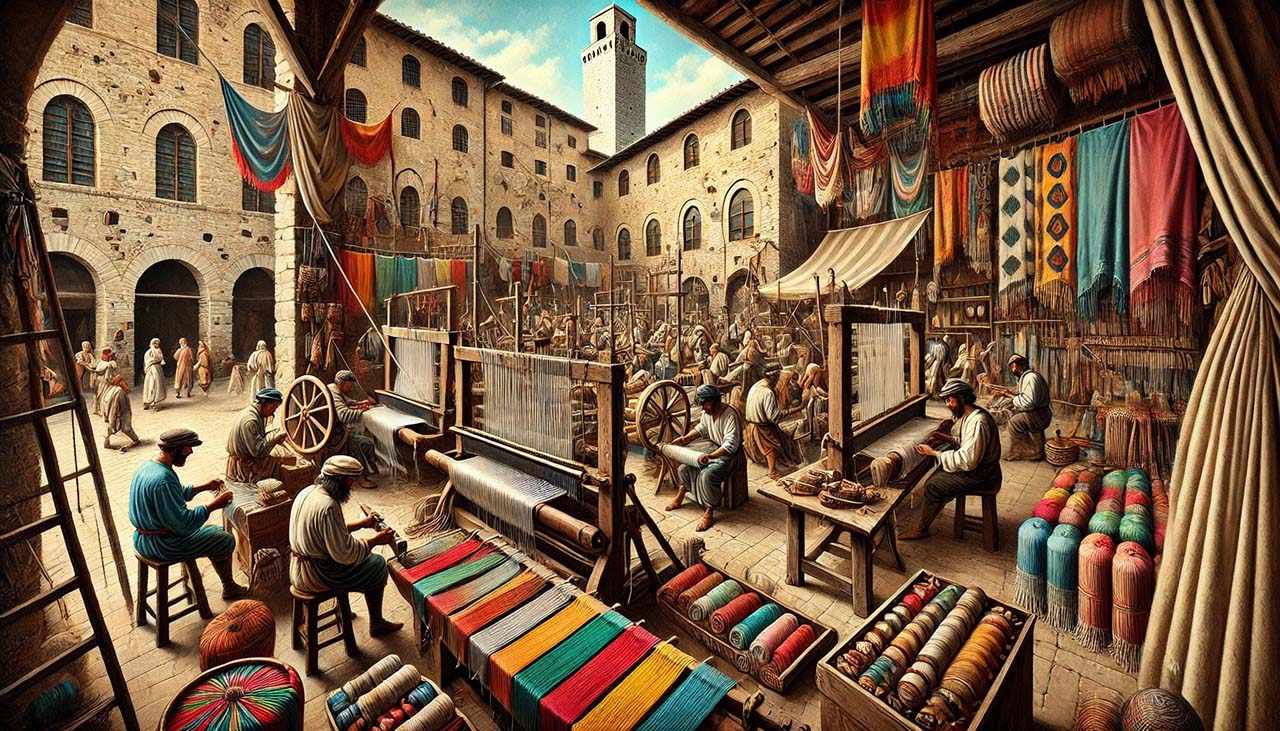

Weavers set up their looms in small workshops or even in open doorways, spinning wool from sheep raised in the surrounding hills. They create cloth that is dyed in bright colors with natural dyes—reds, blues, and greens—that will be sewn into clothing. Tanners work with hides, soaking them in vats of urine and tannins to make leather for shoes, belts, and harnesses. The air is filled with the sounds and smells of industry as the village awakens.

The Morning Pulse of Commerce

As the sun climbs higher in the sky, the Piazza della Cisterna, the central square of the village, begins to hum with life. This square, named after the ancient stone well at its center, serves as the village’s bustling market hub. Merchants and vendors, both local and those who have traveled from neighboring towns, start setting up their stalls. They unfurl their colorful awnings, designed to shield them from the harsh sun or unexpected rain, and meticulously arrange their goods to attract the attention of passersby.

Vibrant Medieval Market in Medieval San Gimignano

The market stalls are a vibrant display of the village’s agricultural and artisanal bounty. Baskets overflow with fresh fruits and vegetables— leafy greens, and fruit glistening with morning dew. Stacks of aged cheeses, wheels of pecorino and rounds of fresh ricotta, sit alongside wooden crates filled with eggs, their surfaces speckled and earthy.

Coils of sturdy rope and bolts of hand-dyed cloth are neatly piled next to handcrafted tools and utensils, their wooden handles smooth from careful carving. Barrels of rich red wine and golden olive oil, the prized produce of the surrounding vineyards and groves, are lined up in neat rows, and slabs of salted meat hang from hooks, enticing shoppers with their savory aroma.

But the market is much more than a place of commerce; it is the social heart of the village. Here, villagers gather not only to buy and sell but to meet, converse, and catch up on the latest news. The market is a melting pot of voices and languages, where gossip and stories flow as freely as the goods being traded.

It’s where news from the outside world filters in, often brought by traveling merchants or pilgrims passing through on their way to Rome or Santiago de Compostela. These visitors bring tales of distant lands, rumors of wars and politics, and news of the latest fashions and customs, connecting the village to the broader currents of medieval life.

Mid-Morning Bustle of Trade and Bargaining

By mid-morning, San Gimignano is fully awake, and the market square is a hive of activity. Farmers from the surrounding countryside, having finished their early morning chores, arrive with carts laden with produce to sell. They barter and haggle over prices with the villagers, who inspect the goods with discerning eyes.

Women, often tasked with managing household supplies, are frequent visitors to the market, moving from stall to stall with woven baskets on their arms. They carefully select ingredients for the day’s meals, choosing fresh vegetables, herbs, grains, and occasionally, a cut of meat for a special occasion.

Craftsmanship and Textile Trade

Meanwhile, the skilled craftsmen of San Gimignano are hard at work in their nearby workshops, contributing to the village’s bustling economy. The village is renowned for its fine textiles, especially its high-quality wool, which is dyed using natural pigments to create vibrant hues of red, blue, green, and yellow.

The weavers, their looms clattering rhythmically, produce bolts of cloth that will be used to make clothing and other goods. These fabrics are a valuable commodity, not just within the village but also in neighboring towns and cities, traded for goods and services. The sound of the loom and the sharp, clear snaps of scissors cutting through cloth add a musical backdrop to the market’s buzz.

Trade Routes Bring Exotic Goods to San Gimignano

Trade is vital to San Gimignano’s prosperity and is deeply embedded in the village’s daily life. Positioned along the Via Francigena, a major pilgrimage and trade route that stretches from Northern Europe to Rome, the village attracts merchants from far and wide. These traders bring with them an array of exotic goods that are otherwise unheard of in this quiet corner of Italy.

Spices such as cinnamon and saffron, precious silks, and other luxury items from distant lands like Asia and the Middle East make their way to the market stalls, where they are eagerly snapped up by the wealthier citizens.

The wealth of San Gimignano is visible in the towering homes of its merchant families, who have grown rich through trade and commerce. These families, always eager to display their status, are frequent patrons of the market, purchasing luxury goods to adorn their homes or as gifts for friends and allies.

The high stone towers that rise above the village—symbols of wealth and power—serve as both defensive structures and status symbols, marking the skyline with the aspirations and rivalries of the merchant elite.

As the morning progresses, the market square remains the pulse of the village, a lively scene of commerce, conversation, and community, embodying the spirit and vitality of medieval life in San Gimignano.

Noon: Pause for Prayer and Rest

By midday, the sun is directly overhead, and the village slows its pace. The church bell rings again, this time for the Angelus prayer, a call to remember the Annunciation and to give thanks. Villagers pause their work to offer a moment of prayer, whether they are in the fields, workshops, or homes. This pause is not just a religious obligation but also a much-needed break in the day’s labor.

Following the Angelus, families gather for the main meal of the day. This meal, typically the largest, is a communal affair, with extended families or groups of neighbors often eating together. The meal might include freshly baked bread, cheese made from goat or sheep’s milk, and a hearty stew made from vegetables, beans, and perhaps some meat if it is available.

In wealthier households, the meal could be more elaborate, featuring roasted meats, pies, and fruit. Wine, often diluted with water, is a common beverage, consumed at every meal. It is not only a staple of the diet but is also considered safer to drink than water, which can be contaminated.

After the meal, there is a period of rest. The intense heat of the midday sun, especially in summer, makes this a good time to seek shade or stay indoors. Some might take a short nap, while others use the time to socialize or catch up on lighter tasks. This siesta is an integral part of daily life, providing a brief respite before the afternoon’s work begins again. For many, it is a time to reflect, pray, or simply enjoy the company of family and friends.

Afternoon in San Gimignano means Back to Work

As the heat of the day begins to wane, the village returns to its work. Farmers head back to the fields to continue their tasks—harvesting crops, repairing fences, or tending to livestock.

The blacksmith’s forge glows red-hot as he continues his work, while the carpenter shapes wood into tools, barrels, and furniture. In the market, traders continue to ply their goods, hoping to make a few last-minute sales before the day ends.

For many children, the afternoon is a time for learning and chores. Boys might learn their fathers’ trades, helping in the fields, workshops, or stalls, while girls assist their mothers with household tasks—cooking, spinning, weaving, and caring for younger siblings.

Education is informal and practical, centered around the skills needed for everyday life. A few children, often from wealthier families, might receive formal education from the village priest or a traveling tutor, learning to read and write Latin, the language of the Church and scholarly texts.

Meanwhile, the village council, composed of respected elders or local leaders, might meet to discuss matters of importance. These meetings, held in the open air or in a designated hall, are crucial for maintaining order and addressing communal concerns.

They might discuss disputes over land or resources, organize repairs to communal buildings or the village well, or plan for upcoming festivals or holy days. Decisions are often made by consensus, with each member having a voice in the proceedings. This self-governance is essential to the village’s stability, ensuring that the needs of the community are met and that justice is upheld.

Despite the relative peace, the period from 1200 to 1300 is also marked by frequent conflicts. Local lords might engage in territorial disputes, and the village could be threatened by raids from rival factions or foreign invaders.

The constant threat of war and conflict means that villagers must be prepared to defend themselves. Some villages, like San Gimignano, are fortified with walls and towers, and the local lord might call upon the men of the village to serve as soldiers or watchmen. This ever-present danger makes daily life uncertain, reminding the villagers that their safety is never guaranteed.

Evening: The Day Winds Down in San Gimignano

As the sun sets, casting long shadows over the hills and vineyards, the village begins to wind down. Farmers return from the fields, artisans close their workshops, and the market comes to a close.

The evening meal is simpler than the midday feast, often consisting of leftovers, bread, and a thin soup or porridge. Families gather around their hearths, sharing stories of the day, discussing plans for the future, and enjoying the rare moments of leisure. The evening is a time for relaxation, a brief respite from the demands of daily life.

For many, the day ends as it began—with prayer. The church bell rings one last time, calling the villagers to evening prayers, the Compline, where they give thanks for the day’s blessings and seek protection through the night.

Faith is a constant companion in their lives, providing comfort and a sense of order in a world that can be harsh and unpredictable. The church, illuminated by candlelight, is filled with the soft murmur of prayers and hymns, a soothing end to a busy day.

After prayers, the village square comes alive with communal activities. Villagers gather to share news, tell stories, and enjoy music and dance. Young men and women flirt and court, children play games, and the elders share tales of the past.

This social time is crucial for maintaining the bonds of community, and reinforcing friendships, alliances, and family ties. Music is a common form of entertainment, with villagers playing simple instruments like flutes, drums, or lutes. Dancing is another popular pastime, with everyone joining in to celebrate the end of another day’s work.

Night: The Medieval Village of San Gimignano Sleeps

As darkness falls, the village settles into silence. The streets are deserted, and the only sounds are the occasional hoot of an owl or the rustling of the wind through the trees. Homes are secured for the night, with wooden shutters drawn and doors bolted.

Families sleep close together, their homes providing a small but sturdy shelter against the outside world. Inside, the hearth burns low, casting a warm glow on the rough stone walls. The village, though small and seemingly isolated, is a world unto itself.

It is a place where life is governed by the rhythms of nature, the cycles of the seasons, and the traditions passed down through generations. Each day brings its challenges and rewards, but through hard work, faith, and the support of the community, the villagers find a sense of purpose and belonging in this medieval world.

They sleep knowing that tomorrow will bring more of the same—the familiar, unending cycle of work and rest, hardship and joy, life and death.

Life in a medieval village like San Gimignano during the 1200s and 1300s was a delicate balance of work, faith, and community, shaped by the natural world and the rigid structures of feudal society.

Despite the hardships and uncertainties, the villagers of San Gimignano found meaning and fulfillment in their daily routines, their faith, and their communal bonds. Their lives were a testament to human resilience and the enduring power of tradition, qualities that continue to define rural life in Tuscany today.

Though centuries have passed, the echoes of medieval village life still resonate in the Italian countryside. The fields that once fed the villagers, the stone towers that stood as silent sentinels, and the cobbled streets that echoed with the sounds of daily life all remain as silent witnesses to a way of life that, while long gone, still informs the character and culture of this beautiful region.

* Find RomeCabs online also on:

- RomeCabs Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RomeCabsToursAndTransfers

- RomeCabs Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.it/romecabs

- RomeCabs Twitter: https://twitter.com/RomeCabs

- RomeCabs Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/romecabs/

- RomeCabs Flickr Photos: https://www.flickr.com/photos/romecabs/

- RomeCabs Recommended on Cruise Critic